By Dr. Tigani Alam and Mohamed Salah

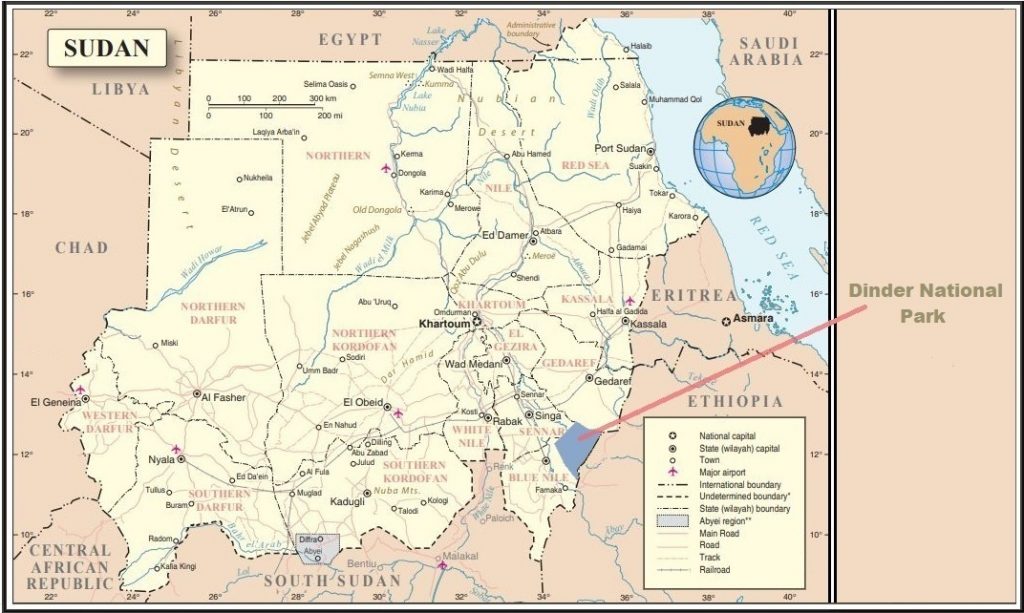

Dinder National Park, located in southeastern Sudan, is an ecological treasure encompassing a diverse range of habitats. It was the first national park in Sudan and was established in 1935 following the London Convention of 1933 for the conservation of fauna and flora in their natural state. Spanning approximately 10,000 square kilometers, the park is characterized by its unique flora and fauna, with the Dinder River carving through its landscape. The park serves as a critical refuge for numerous species, including a variety of resident and migratory birds, ungulates, and carnivores. The Dinder River, a vital component of the park’s ecosystem, contributes to the formation of wetlands and floodplains, fostering a dynamic and interconnected environment. The park’s vegetation ranges from riverine forests to savannah woodlands, creating a mosaic of habitats that support a high level of biodiversity. The park is open to tourists and visitors from Decembers to May.

Location and Size

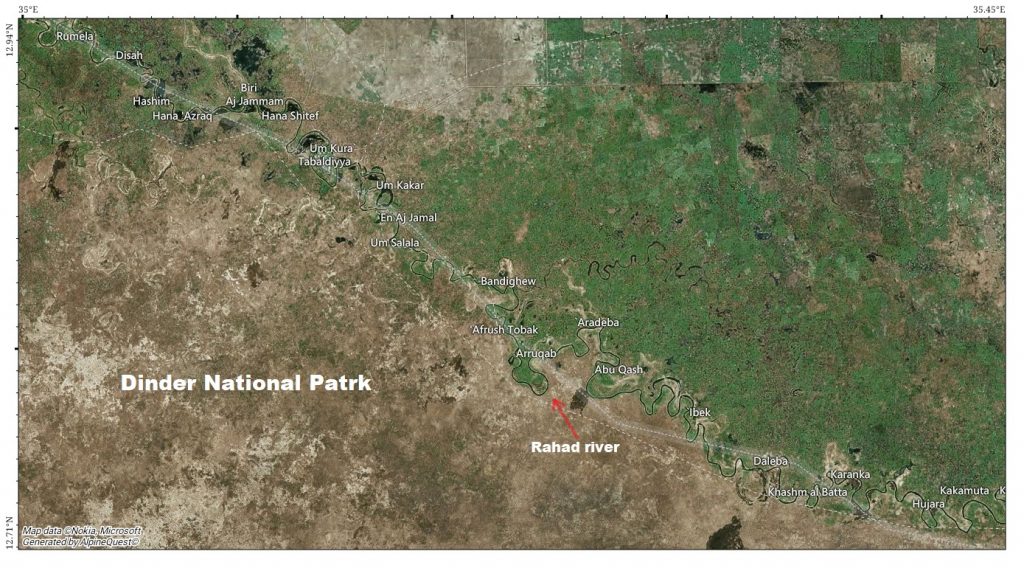

Dinder National Park is situated in the southeast of Sudan on the Sudanese-Ethiopian border between latitudes 11.45 and 12.50 North and longitudes 36.00 and 34.40 East. Dinder National Park spans across multiple Sudanese states. The majority of its area lies within Sennar State. The north and northeast of the Rahad River, within the park’s boundaries, is El Gedaref State. Additionally, the south-western and southern border areas of the park extend into the Blue Nile State. The park is bound to the east and southeast by the Ethiopian border. The park was established in 1935, covering an area of 6,960 square kilometers, and in 1978, President Jaafar Nimeiry expanded its size to 10,291 square kilometers to keep mechanized agriculture away from the northern and western boundaries of the park.

Road to Dinder National Park

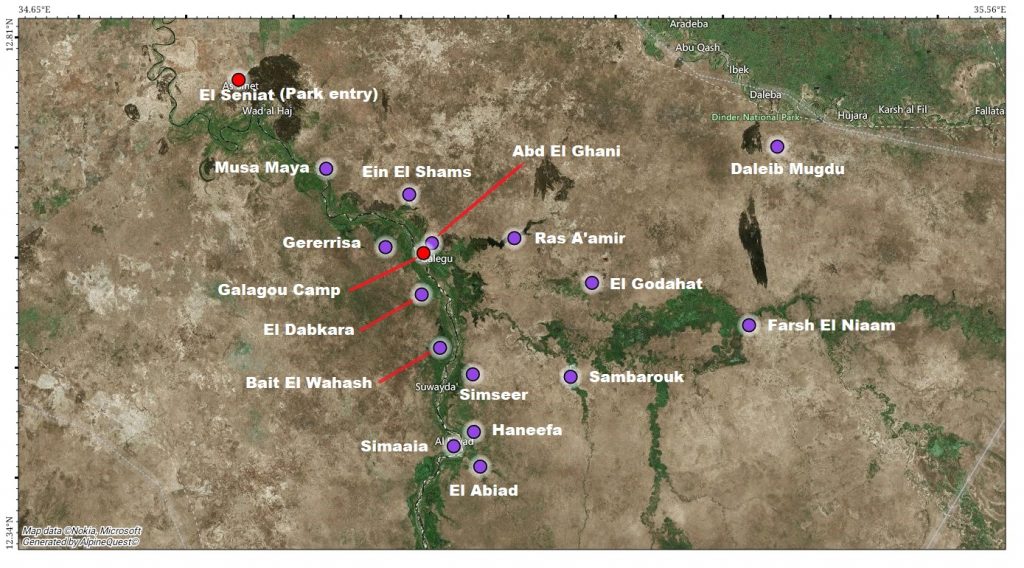

The road journey from Khartoum to Dinder National Park cover approximately 600 kilometers, directing travelers southeastward along the Khartoum-Sennar Highway. The route encompasses notable towns like Wad Madani, Sennar, Singa, and Dinder town. Dinder town is a major waypoint in the journey, housing both the wildlife conservation administration and park administration. Usually, visitors spend the night in Dinder town before heading eastward towards Dinder National Park.

From Dinder town, a four-hour drive over rough terrain, covering 185 kilometers, leads to Galagu camp within the park. This final leg of the journey unveils the untamed beauty of Dinder National Park, providing an adventurous entrance to the heart of the wilderness.

Climate

Dinder National Park experiences a two-season climate, with a hot and wet rainy season occurring from May to November, and a cold dry season lasting from December to March. The average annual precipitation in the park varies, ranging from 800 to 1000 mm in the southeast part, and from 600 to 800 mm in the north. The average maximum temperature is 30°C from November to February, rising to 38°C from March to the beginning of the rainy season.

During the rainy season, the park is impacted by the interaction of central Sudan rains and atmospheric conditions from West Africa. The convergence of air masses, including those from the Atlantic Ocean and the Kanga region, contributes to dynamic precipitation patterns within the park. The influence of the Indian Ocean can either enhance or reduce the intensity of seasonal rains. Rain lines initially move from west to east, then shift northeastward and southeastward, enveloping Ethiopian territories.

Ecosystem and Plants Diversity in Dnider National Park

The Dinder National Park features a network of rivers, seasonal watercourses, and meadows (expansive permanent water ponds, locally known as ‘Mayas.’) These create environments along riverbanks that are inherently rich in vegetation. This ecological richness acts as a magnet, attracting diverse wildlife that either feeds on the flourishing vegetation or seeks shelter within these plants. This is the rationale behind declaring this area as a nature reserve.

Dinder National Park comprises three main ecosystems: El Dahara (woodland), the riverine ecosystem, and Mayas (meadows). Within these ecosystems, the flora demonstrates adaptability to diverse environmental conditions, resulting in variations in vegetation cover between them. The park contains 49 tree and shrub species, along with 68 grass species. several of these tree species are endangered and facing the risk of extinction. These include, among others, Adansonia digitata (Tabaldi), Albizia aylmeri (Sereira), and Combretum harmannianum (Habeel).

– Mayas (Meadows)

Mayas is the most important ecosystem in Dinder National Park, serving as the primary drinking water source for wildlife during the dry season. With over 40 Mayas in the park, ranging in size from 200 square meters to 4.5 square kilometers, these water bodies are commonly known as Oxbow Lakes in English. Formed in flat, low-lying plains near the confluence of rivers with other bodies of water, these meandering lakes originate from former river channels abandoned over time due to changes in the river’s course.

Mayas receive their water during the rainy season from various sources, including direct flow from the rivers and main watercourses (Galeguo and Masaweek) through Saggai, small streams, and watercourses near Mayas, as well as direct rainfall. Saggai is the local name for the watercourses that contribute to filling Mayas.

Along the banks of Mayas, the common trees including Acacia nilotica (Sunt), Acacia Polycantha (Kakamout), Acacia Sieberiana (Kuk), Crateva adansonii (Dabkar), and Zizphus sp. (Sidir and Nabag El Feel). Continuing along the banks of both Mayas and Saggai, there are lush green grasses, particularly Echinochloa sp. grasses, extending for several kilometers. These grasses serve as primary food source for herbivorous animals during the dry season. Locally, this environment is known by name ‘Farish’.

In the Botana and nearby areas, the term ‘Dinder,’ synonymous with ‘Oxbow,’ which means a perennial water source. The Dinder River derives its name from this term, emphasizing the presence of Oxbow lakes within its basin. These lakes are crucial water sources for communities along the Dinder River, especially during the dry season. It is from this river that the park takes its name.

– Riverine Ecosystem

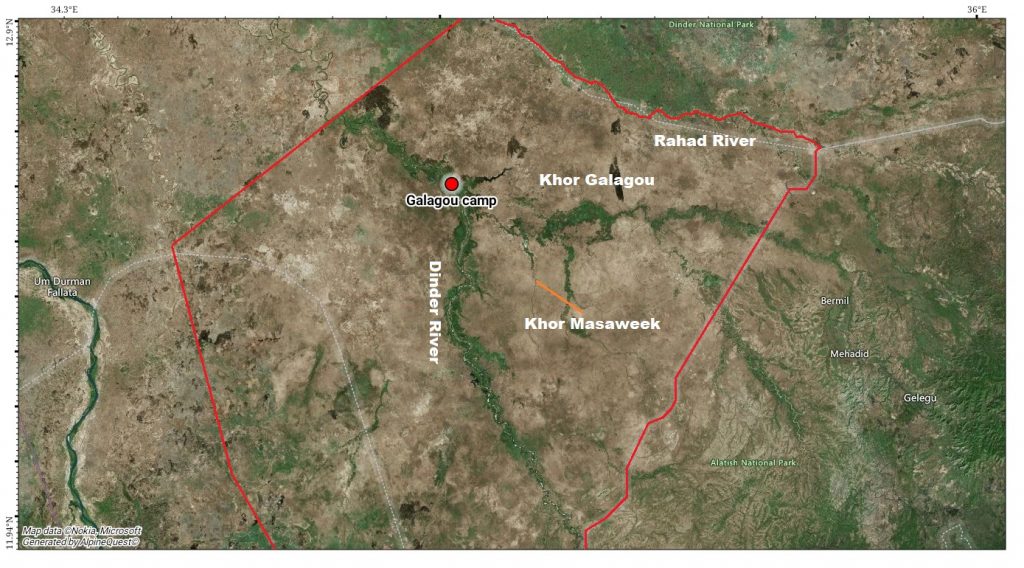

Dinder and Rahad are the main rivers in Dinder National Park, accompanied by many seasonal streams, forming a riverine ecosystem along their banks – a web of rich habitats within the park, fostering a diverse array of flora and fauna.

These rivers originate from the Ethiopian highlands. They are seasonal rivers and flow from June to November. Despite being small rivers in Ethiopia, as they flow towards Sudan, they gather more water from numerous streams and become significant tributaries to the Blue Nile River during the flooding season. Locally, these streams are known by the name ‘Khor.’ The main streams, or ‘Khors,’ in the park include Khor Galagou, which confluences with the Dinder River at Galagou camp, and Khor Masaweek, which confluences with the Dinder River north of Simseer Maya.

The riverine ecosystem is characterized by a dense and rich variety of plant life along the banks, forming a multi-layered cover. Common plants in the upper region include Hyphaene thebaica (Dom), Acacia sieberiana (Kuk), Acacia nilotica (Sunt), Gardenia lutea (Abu Gawi), Ficus sycomorus (Gomeiz), Tamarindus indica (Aradeib), and Crateva adansonii (Dabkar), while the lower area contains Tamarix nilotica (Tarfa), Ziziphus abyssinica (Nabag El Feel), Ziziphus spina-christi (Sidir), and Mimosa pigra (Shajarat El Fas or El Seit El-Mostahia).

Despite being seasonal, the Dinder and Rahad rivers host numerous permanent ponds within their basins, even during the dry season. These ponds provide a stable habitat for aquatic animals such as fish, turtles, and crocodiles, serving as an important drinking water source for wildlife and a feeding habitat for waterbirds.

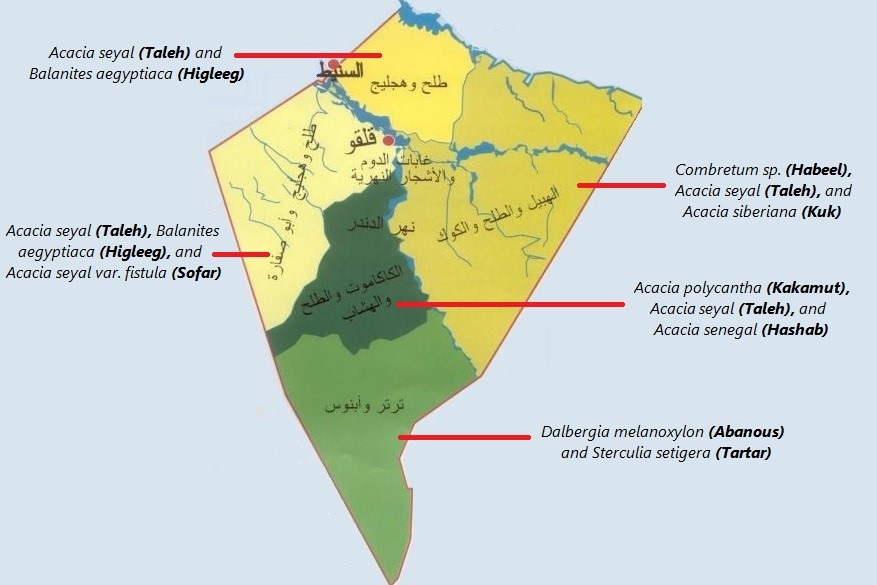

– El Dahara (Woodland)

Dahara is the largest ecosystem in the park, often referred to as the Acacia seyal-Balanites ecosystem due to the prevalence of these dominant trees. Common tree species in El Dahara include Acacia seyal (Taleh), Balanites aegyptiaca (Higleeg), Combretum sp. (Habeel), and Acacia seyal var. fistula (Safar or Taleh Abiad), among various others. Notably, these trees, excluding B. aegyptiaca, shed their leaves during the dry season.

In the southern region towards the Ethiopian border, which experiences higher rainfall, the climate transforms into a high-rain savannah habitat. This area introduces additional species like Sterculia cieral (Tartar), Dalbergia melanoxylon (Abanos), Diospyros mespiliformis (Gugahan), Terminalia brownii (Subakh) and Anogeisous leiocarpus (Sahab). The soil in Aldahra, a part of this ecosystem, is characterized by dry, cracked clay, posing access challenges during the rainy season.

Funa (Animals Diversity)

Natural History Notes to Dinder National Park Funa

Dinder National Park is an ecological reservoir in Sudan boasts a diverse array of wild animals. It diverse ecosystems, including woodlands, riverine forest, Mayas and open savannahs provide habitats for a range of wildlife from mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes to Arthropods. The park’s location in southeastern Sudan places it within Sudaian savanna ecoregion, animals found in park are representative of its species.

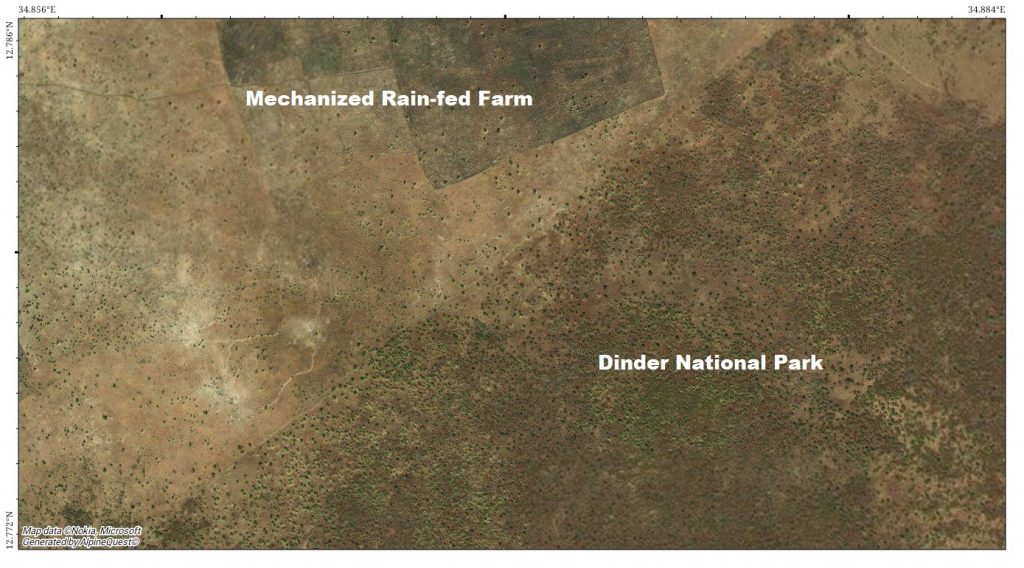

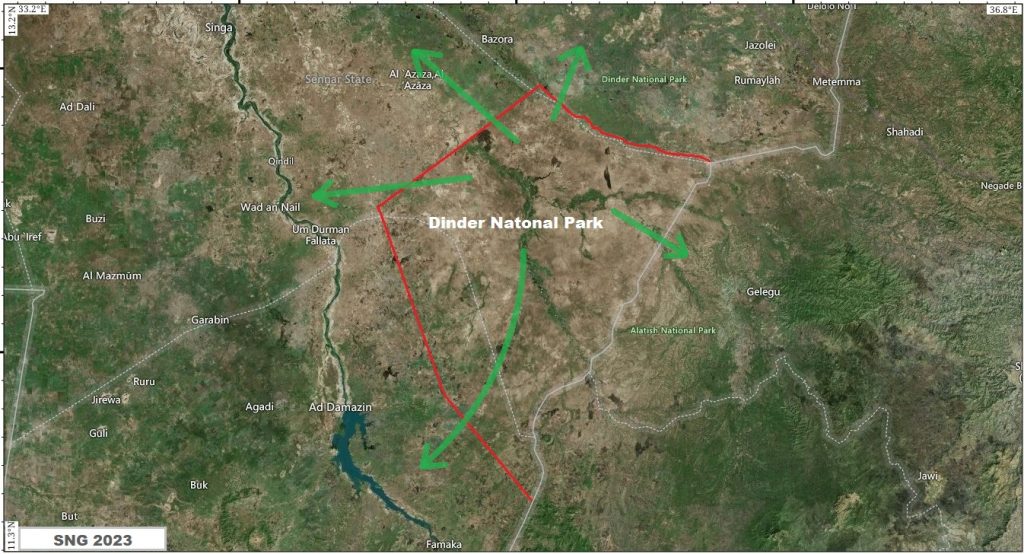

Despite its large size, Dinder National Park has witnessed the disappearance and extinction of many animals over the years. hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius) and black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) were last recorded in the early 20th century, while the lelwel hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus lelwel) was last documented in the 1950s. Since Sudan gained independence, inadequate management has further exacerbated the extinction and decline of numerous species in the park, particularly between 1980 and 2000. Various factors contributed to this decline, including excessive hunting, the expansion of mechanical rain-fed agriculture into the park’s boundaries which disrupting migration routes and destroying the wet-season habitat of various animals, and climate changes. The period between 1980-1984, marked by severe drought in Kordofan and Darfur, which lead to widespread displacement, with significant migrations from western Sudan to the park’s boundaries, increasing pressure on wildlife inside the park.

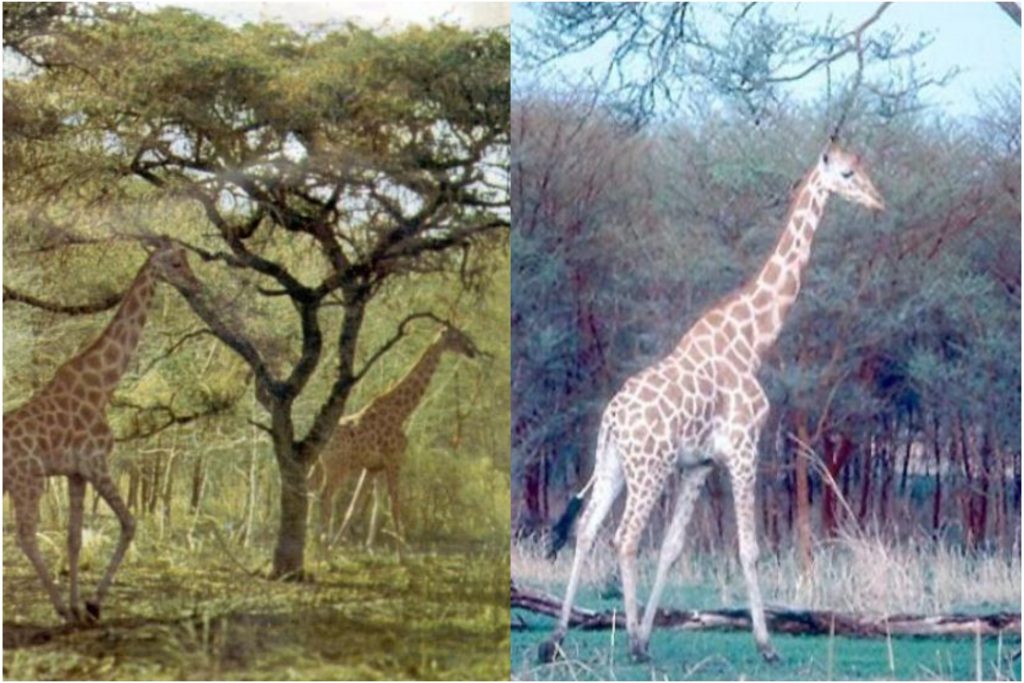

Animals that have gone extinct in the park include soemmerring’s gazelle (Nanger soemmerringii), once one of the most common antelopes in the park. It was last seen in 1966, and its extinction is primarily attributed to excessive hunting during migration to the wet season habitat in the Botana Plain. Nubian giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis camelopardalis) was last observed in 1984, and its extinction is linked to the extension of mechanical rain-fed farms to the park boundaries, resulting in the destruction of wet-season habitat and large-scale hunting. The last sighting of the tora hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus tora) in Dinder National Park was in 1999. Leopards (Panthera pardus) have not been recorded in the park for a significant period, likely due to excessive hunting driven by demand and the high value of leopard skin. The cultural association of leopard skin with high societal rank, particularly in the creation of traditional shoes (Markoub), has contributed to the depletion of leopard populations in the park. However, in 2017, leopards were recorded in Alatish National Park, which forms a transboundary conservation area with Dinder National Park. According to wildlife guards, leopards are still present in Dinder National Park, but these records are not confirmed. Additionally, cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) have not been observed in the park for a long period.

Elephants (Loxodonta africana) are historically believed to migrate to Dinder National Park from Ethiopia during the wet season, a belief shared with Alatish National Park, which believes the elephants visit the park during the wet season from Dinder. Some wildlife guards have reported a resident herd of seven elephants near Tabia since 2008, a fact reaffirmed by the guards in 2013 in the southeastern part of the park. Nabi mentioned the presence of a herd of elephants with moderate ivory in the park in 1956. Footprints were seen in 2012 and again in March 2023 in Khor Galaguo further support the presence of this small herd. The movement of these small herd of elephants between Dinder and Alatish National Parks contributes to potential misunderstandings about the status and distribution of elephants in both parks.

Even the currently existing animals in the park have suffer a significant decline in the numbers of some species. For example, the Tiang (Damaliscus lunatus tiang), which its population was estimated at 9,000 animals in 1972, has drastically decreased and the last photo record of Tiang in the park with us dates back to 2008. However, according to the park guards, some individuals are still present in Dinder national park. The Bohor Reedbuck (Redunca redunca) which once Dinder national park have boasted the largest population in world of it and estimated at around 120,000 animals, has also experienced a severe decline and According to a 2021 survey conducted in the core area, representing approximately 30% of the reserve’s total area (about 3,000 square kilometers), the population in that area is now around 6,000 animals.

Despite the disappearance of many animal species and the decline in the numbers of some, Dinder National Park remains a refuge for numerous endangered animals. These include lions, gazelles, various antelope species, and a variety of birds such as the Arabian Bustard, Martial Eagle, White-backed Vulture, Lappet-faced Vulture, and Spotted Eagle.

Furthermore, several new species have been discovered inside the park in recent years. These species include the kob and bush pig.

Mammals of Dinder National Park

Dinder National Park hosts a diverse array of mammals, with a total of 32 medium and large-sized species distributed across seven taxonomic Orders. Additionally, seven species of bats have been confirmed to inhabit the park. While limited information is available about the diversity of small mammals ongoing research reveals the potential for new discoveries even within the large mammals. Notably, the bush pig (Potamochoerus larvatus) was recorded and documented for the first time in 2021, and the Kob (Kobus kob) was first recorded in 2018.

Order Chiroptera (Bats: 7 speceis)

Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight, characterized by the elongation of their forelimbs, forming wings with a thin membrane of skin that creates a dynamic surface for efficient flight. The order Chiroptera, to which bats belong, is divided into two suborders: Megachiroptera, consisting of fruit-eating bats, and Microchiroptera, encompassing insect-eating bats. Another interesting adaptation within the Microchiroptera suborder is echolocation. With poorly developed eyesight primarily used for detecting sunset and darkness, bats use reflected ultrasonic sounds to create a detailed picture of their surrounding environment, aiding in prey capture.

All bat species in Sudan are locally known as “Abu Al Watwat” or “Khofash.” The exact number of species in Dinder National Park is unknown, and only a few studies have mentioned bat diversity in the park. A study conducted in the nearby Alatish National Park recorded a total of 21 bat species.

Family Pteropodidae (Old World Fruit Bats)

– Epomophorus labiatus Epauleted Fruit Bats

Family Rhinolophidae (Horseshoe Bats)

– Rhinolophus landeri Lander’s horseshoe bat

Family Megadermatidae (False Vampire Bats)

– Lavia frons Yellow-winged Bat

Family Nycteridae (Slit-faced Bats)

– Nycteris thebaica Egyptian Slit-faced Bat

Family Vespertilionidae (Vesper Bats)

– Glauconycteris argentata Common Butterfly Bat

– Glauconycteris variegata Variegated Butterfly Bat

– Scotophilus nigrita Giant House Bat

Order Primates (Apes, Monkeys, Human, Galagos, Lemurs, and allies: 4 species)

The order Primates comprises a diverse group of mammals characterized by the irforward-facing eyes allowing stereoscopic vision, grasping hands with opposable thumbs, and relatively large brains compared to body size, Nails rather than claws in most digits.

Primates are also known by intricate social structures, long gestation periods, strong parent-offspring bonding, and prolonged infancy.

Social structures vary among species, ranging from solitary to complex social groups. Communication is often intricate, involving vocalizations, facial expressions, and body language.

Primates are typically arboreal, adapted for life in trees, but some have adapted to terrestrial habitats. Within the order Primates, there are two main suborders: Strepsirrhini (lemurs and lorises) and Haplorhini (tarsiers, monkeys, and apes). Haplorhini further divides into two infraorders: Platyrrhini (New World monkeys) and Catarrhini (Old World monkeys and apes)

Family Cercopithecidae (Old World Monkeys)

– Papio anubis Olive Baboon (Tegel)

– Erythrocebus poliophaeus Moustached Monkey or Blue Nile Patas (Abu Sirwal or Ablang)

– Cercopithecus aethiops Grivet Monkey (Nasnas)

Family Galagidae (Galago or Bushbaby)

– Galago senegalensi Senegal Lesser Bushbaby (Tng)

Order Pholidota (Pangolin: 1 species)

Pangolins, also known as scaly anteaters, are characterized by their distinctive appearance, covered in protective armor-plated scales made of keratin that envelop all upper parts of their bodies. These nocturnal, insectivorous creatures are well-adapted for digging. They lack teeth and have long, sticky tongues covered in saliva to consume ants and termites which represent their primary food source. When threatened, pangolins rolling themselves into a tight ball, exposing only their tough scales. Pangolins inhabit forests and forest savannas across Africa and Asia, with four species in Africa and four in Asia.

Family Manidae

– Smutsia Temminckii Ground Pangolin (Abu Girif), not recorded recently, probably due to its shy habits and nocturnal behavior. It is also mentioned in old reports about park diversity. Specimens have been collected from Sennar, and Yalden mentioned the presence of this species in Ethiopia, relying on specimens collected from the Sennar region near borders with Ethiopia which is Dinder National Park.

Order Lagomorpha (1 species)

The order Lagomorpha is characterized by distinctive dentition, featuring two pairs of upper incisors, one behind the other. This order includes two families: Leporidae (hares and rabbits) and Ochotonidae (pikas). Lagomorphs are herbivores, equipped with hind limbs adapted for powerful propulsion, enabling swift running and leaping to evade predators. Hares and rabbits are known for their rapid reproduction, but they differ in morphology and behavior. Hares, characterized by long hind leg, short wooly tail and long ears, do not dig burrows like rabbits. Instead, they hide between bushes and rocks during the day. They are displaying a solitary lifestyle and are primarily active at night.

Family Leporidiae (Hares and Rabbits)

– Lepus capensis Cape Hare (Arnab), not found in the core area of the park but appears to be present in the northern boundaries, confirmed from Sennar.

Order Rodentia (Rodents: 2 species)

Rodents are gnawing mammals that comprise about 40% of mammals and include squirrels, rats, mice, gerbils, porcupines etc. They are characterized by two pairs of sharp incisors used for cutting and gnawing their food plants specially fruits and pods.

Family Sciuridae (Squirrels)

– Xerus erythropus African Ground Squirrel (Sabara), not recorded from the core area of the park, but it was confirmed in the northern part of the park on the bank of the Rahad River near a village that adjoins the park’s northern boundary.

Family Hystridae (Porcupines)

– Hystrix cristata North AfricanCrested Porcupines (Abu Shoak)

Order Carnivora (Carnivores: 11 species)

The order Carnivora encompasses a diverse group of mammals characterized by their diet mainly meat. These animals have evolved many adaptations to excel in predation, reflecting their role as apex predators in various ecosystems regulating and controlling other animals population. One key adaptation is their dentition, featuring sharp and pointed teeth designed for grasping, tearing, and cutting flesh. Canines are often well-developed, aiding in the capture and killing of prey, while carnassial teeth are adapted for efficient shearing of meat. senses are acute, Keen eyesight, acute hearing, and an acute sense of smell contribute to their ability to detect prey, often from a distance. Many carnivores have evolved nocturnal version, allowing for efficient hunting during night.

Social structures among carnivores are diverse. Some species, like lions, exhibit group living with cooperative hunting strategies, while others, like solitary leopards, rely on stealth and ambush. Specialized hunting techniques, such as pack hunting, ambush predation, or pursuit predation, are common among carnivores.

Family Canidae (Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs)

– Canis lupaster African wolf

Family Felidae (Cats)

– Panthera leo Lion ( Asad)

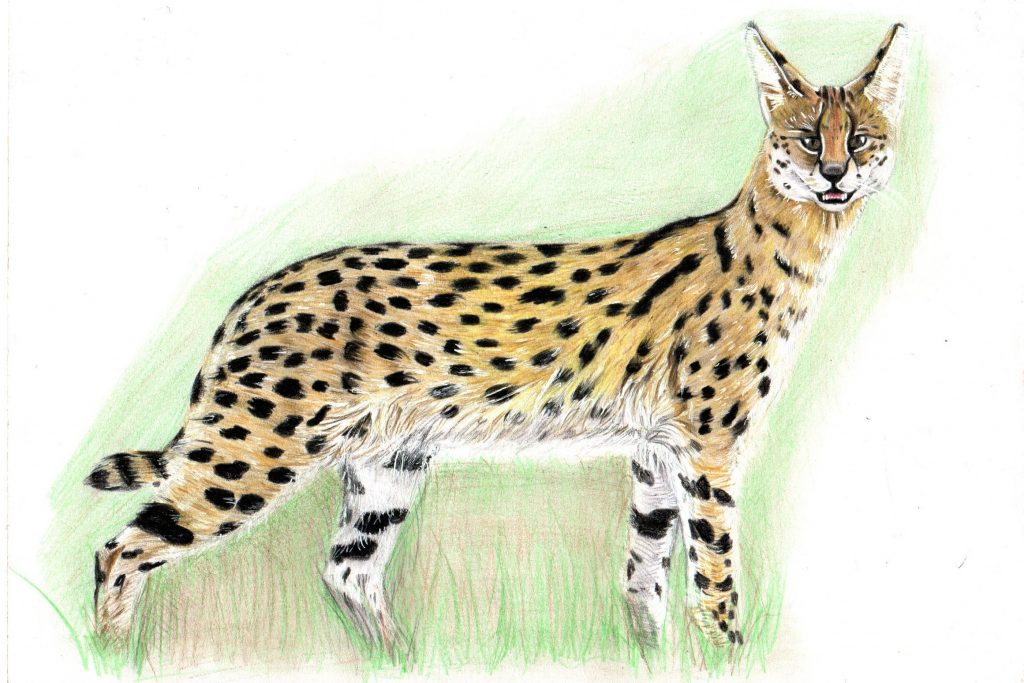

– Leptailurus serval Serval (Abu A’aj)

– Felis silvestris Wild Cat (Kadis El khala)

Family Mustellidae (Weasels, Polecats, Otters, Ratel and allies)

– Mellivora capensis Ratel or Honey Hadger (Abu Drunbal or Abu El Kea’aeb)

Family Viverridae (Genets, Linsangs, Civets)

– Genetta genetta Common Genet (Allia or El Kameir)

– Civettictis civetta African Civet (Zabad or Kadis El Zabad)

Family Hyaenidae (Hyaenas, Aardwolf)

– Hyaena hyaena Striped Hyaena (Marfa’in)

– Crocuta crocuta Spotted Hyaena (Marfa’in)

Family Herpestidae (Mongooses)

– Ichneumia albicanda White-tailed Mongoose (Nimis)

– Herpestes ichneumon Egyptian Mongoose (Nimis or Abu Lasloss)

Order Tublidentata (Aardvark: 1 species)

The order Tubulidentata contain a single extant species, the aardvark. Aardvarks are nocturnal, burrowing mammals native to Africa. They characterize by a robust body, a long snout, and a distinctive tubular tongue specialized for capturing and consuming ants and termites. Notably, aardvarks lack incisors or canines, and their teeth are reduced. Aardvarks have powerful limbs and sharp claws used for digging burrows and excavating insect nests. Their ears are large, providing excellent hearing, and they possess a keen sense of smell. Despite their pig-like appearance, aardvarks are taxonomically unique, representing a distinct evolutionary branch.

Family Orycteropodidae

– Orycteropus afer Aardvark (Abu Delaf)

Order Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates: 12 species)

The order Artiodactyla comprises a diverse group of mammals characterized by an even number of functional toes on each foot. This taxonomic order includes several suborders: Suina (pigs), Tylopoda (camels), Ruminantia (ruminants), and Whippomorpha (hippopotamus and relatives). Artiodactyls are herbivores with a complex digestive system, often featuring a multi-chambered stomach that aids in the fermentation of plant material. They play crucial ecological roles as grazers, browsers, and seed dispersers, contributing to the dynamics of diverse ecosystems globally. The adaptability of artiodactyls is evident in their evolutionary success, allowing them to thrive in a variety of environments, ranging from deserts and open grasslands to dense forests and high mountains.

Family Suidae (Pigs and Hogs)

– Phacochoerus africanus Common Warthog (Hallouf)

– Potamochoerus larvatus Bush Pig

Family Bovidae (Bovoids)

– Syncerus caffer African Buffalo (Gamous)

– Tragelaphus strepsiceros Greater kudu (Njalt)

– Tragelaphus scriptus Bushbuck (Abu Nabah)

– Sylvicapra grimmia Common Duiker (Um Tagdom or Um Dik dik)

– Eudorcas tilonura Heuglin’s Gazelle (Um Sir)

– Ourebia ourebia Oribi (Moor)

– Redunca redunca Bohor Reedbuck (Bashmat)

– Kobus kob leucotis/ thomasi? Kob (Hamraya)

– Kobus ellipsiprymnus defassa Defassa Waterbuck (Katnmbour)

– Hippotragus equinus Roan Antelope (Abu Urf)

Birds of Dinder National Park

Dinder National Park have a rich avian diversity, serving as a sanctuary for numerous bird species and playing a crucial role in bird conservation, protecting both migratory and endemic species. Approximately 231 bird species have been confirmed within the park, with the potential for additional discoveries in the future.

The list of bird species found in Dinder National Park is primarily based on direct observations and photos by the author, as well as recorded species in trusted publications. Exclusions were made for species mentioned in publications that fell outside their normal distribution range, often resulting from misidentifications without supporting evidence. Despite this, the park appears to be even more diverse, with the likelihood of adding species to the list, especially as many studies have focused on water birds and larger species neglected to woodland. The limited focus on avian diversity during the wet season which characterized by the migration of many birds from South to North for breeding will added more birds species to the list and further underscores the need for comprehensive research. Additionally, the poor studied riverine forest south of Galagou camp and the better woodlands and hills near the Ethiopian border add another potential for the discovery of many species in Dinder National Park.

Thirteen of birds species found in Dinder national park face the risk of extinction. The only bird not recently recorded in the park is the Black-crowned Crane (Balearica pavonina), which appears to be extinct from the park, with a global population decline (IUCN Status: Vulnerable).

List of Birds in Dinder National Park

Non-passerine Order

– Common Ostrich Struthio camelus (Nea’am)

Family Numididae

– Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris (Gedad El Wadi)

Family Phasianidae

– Clapperton’s Francolin Guttera verreauxi (Kuweir)

– Fulvous Whistling-duck Dendrocygna bicolor (Um Sai Sai)

– White-faced Whistling-duck Dendrocygna viduata (Um Sai Sai, Um Chalilii)

– Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiac (Wizzin)

– Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea

– Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis (Wizzin El Fakag, Fakag)

– Comb Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos (Um Teena, Um Garen)

– African Pygmy-goose Nettapus auritus

– Garganey Spatula querquedula

– Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata

– Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis (Ghattas)

– European Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur (Buorgiatt, Gumri)

– Mourning Collared-dove Streptopelia decipiens (Gumri, in some areas in Sudan the local name is ‘Dabas’ but usually this name uses to Speckled Pigeon)

– Red-eyed Dove

Streptopelia semitorquata

– Ring-necked Dove Streptopelia capicola (Gumri)

– Vinaceous Dove Streptopelia vinacea (Gumri)

– Laughing Dove Spilopelia senegalensis (Gumri)

– Black-billed Wood Dove Turtur abyssinicus

– Namaqua Dove Oena capensis (Balom)

– Bruce’s Green Pigeon Treron waalia

Note: Speckled Pigeon (Columba guinea) not confirmed from the core area of the park but confirmed from Dinder town for that it’s not include in the list.

– Four-banded Sandgrouse Pterocles quadricinctus (Gata)

Family Caprimulgidae

– Long-tailed Nightjar Caprimulgus climacurus (um Brishtii, Um El Ra’aian, in some area the local name is ‘Hamad Labat’ but this name is also uses to coursers)

Family Apodidae

– African Palm Swift Cypsiurus parvus (Grin Hashash)

– Little Swift Apus affinis (Grin Hashash)

– Common Swift Apus apus (Grin Hashash)

– Senegal Coucal Centropus senegalensis (Burbuor)

– White-browed Coucal Centropus superciliosus (Burbuor)

– Levaillant’s Cuckoo

Clamator levaillantii

– Great Spotted Cuckoo Clamator glandarius (Um Takashu)

– Klaas’s Cuckoo Chrysococcyx klaas

– Diederik Cuckoo Chrysococcyx caprius

– Common Moorhen Gallinula chloropus (Mar’aa)

– Black-bellied Bustard Lissotis melanogaster (Um Akkar)

– Arabian Bustard Ardeotis arabs (Hubara)

– Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer (Abu Si’an, Abu Kharita)

– Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis

– Black Stork Ciconia nigra

– Abdim’s Stork Ciconia abdimii (Simbria, Kaljo)

– African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus (Abu Garguor)

– Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia microscelis

– White Stork Ciconia ciconia (Bagbar)

– Saddle-billed Stork Ephippiorhynchus senegalensi (Wad El Mairam, Abu Miebar)

Family Threskiornithidae

– African Spoonbill Platalea alba (Abu Mel’aga)

– Eurasian Spoonbil Platalea leucorodia (Abu Mel’aga)

– African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus (Nia’ga)

– Hadada Ibis Bostrychia hagedash (A’nz El Bhar)

– Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus (Nia’ga)

Family Ardeidae

– Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus

– Black-crowned Night-heron Nycticorax nycticorax

– Green-backed Heron Butorides striata

– Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides

– Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis (Tair El Baggar, Abu El Riheiu)

– Grey Heron Ardea cinerea (Habib Bla’a El Dabieb, Wag)

– Black-headed Heron Ardea melanocephala (Habib Bla’a El Dabieb, Wag)

– Goliath Heron Ardea goliath

– Purple Heron Ardea purpurea (Habib Bla’a El Dabieb)

– Great White Egret Ardea alba

– Yellow-billed Egret Ardea brachyrhyncha

– Little Egret Egretta garzett (Tair El Baggar)

Family Scopidae

– Hamerkop Scopus umbretta (Um Ebeid Allah)

Family Pelecanidae

– Pink-backed Pelican Pelecanus rufescens (Bag’a)

– Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus (Bag’a)

Family Phalacrocoracidae

– Long-tailed Cormorant Microcarbo africanus (Ghattas)

– Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo (Ghattas)

Family Anhingidae

– African Darter Anhinga rufa (Gagaa)

Family Burhinida

– Senegal Thick-knee Burhinus senegalensis (Karrawan)

– Spotted Thick-knee Burhinus capensis (Karwan)

Family Pluvianidae

– Egyptian Plover Pluvianus aegyptius

Family Recurvirostridae

– Black-winged Stilt Himantopus himantopus (Abu Taweela)

Family Charadriidae

– Common Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula

– Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius

– Spur-winged Lapwing Vanellus spinosus (Sugud)

– Black-headed Lapwing Vanellus tectus

Family Rostratulidae

– Greater Painted-snipe Rostratula benghalensis

Family Jacanidae

– African Jacana Actophilornis africanus (Tair El Shuluk, Tair El Sateeb)

– Lesser Jacana Microparra capensis

Family Scolopacidae

– Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa

– Ruff Calidris pugnax (Gubarkal. the name is also use to all waders species in flocks)

– Curlew Sandpiper Calidris ferruginea

– Little Stint Calidris minuta

– Common Snipe Gallinago gallinago (Girwil, it also uses to small waders)

– Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos

– Green Sandpiper Tringa ochropus

– Spotted Redshank Tringa erythropus

– Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia

– Common Redshank Tringa totanus

– Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola

– Marsh Sandpiper Tringa stagnatilis

Family Glareolidae

– Collared Pratincol Glareola pratincola

Family Laridae

– Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus (Nawras)

– Gull-billed Tern Gelochelidon nilotica

– White-winged Tern Chlidonias leucopterus

– Pearl-spotted Owlet Glaucidium perlatum (Boma, Tiu ‘mainly Kordofan’)

– Greyish Eagle Owl Bubo cinerascens (Boma)

– Verreaux’s Eagle Owl Bubo lacteus (Boma)

Family Pandionidae

– Osprey Pandion haliaetus (Boaj)

Family Elanidae

– Scissor-tailed Kite Elanus caeruleus

Family Accipitridae

– African Harrier-hawk Polyboroides typus

– Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus (Rakhama)

– Bateleur Terathopius ecaudatus

– Brown Snake-eagle Circaetus cinereus

– White-headed Vulture Trigonoceps occipitalis (Killin)

– Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus (Killin)

– White-backed Vulture Gyps africanus (Killin)

– Rüppell’s Vulture Gyps rueppell (Killin)

– Lappet-faced Vulture Torgos tracheliotos (Killin)

– Martial Eagle Polemaetus bellicosus

– Long-crested Eagle Lophaetus occipitalis (Abu A’lwan)

– Greater Spotted Eagle Clanga clanga

– Tawny Eagle Aquila rapax

– Verreaux’s Eagle Aquila verreauxii

– Wahlberg’s Eagle Hieraaetus wahlbergi

– Dark Chanting Goshawk Melierax metabates (El Sagur El Abyad)

– Gabar Goshawk Micronisus gabar (Abu El Sigair)

– Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus

– Pallid Harrier Circus macrourus (Abyad Labn)

– Shikra Accipiter badius

– Little Sparrowhawk Accipiter minullus

– African Fish Eagle Haliaeetus vocifer (El Boli)

– Black Kite Milvus migrans (Hidaya)

– Yellow-billed Kite Milvus aegyptius (Hidaya)

– Grasshopper Buzzard Butastur rufipennis

– Red-necked Buzzard Buteo auguralis

– Speckled Mousebird Colius striatus (Sheikh El Toyor)

– Blue-naped Mousebird Urocolius macrourus (Gmbar Gmboor Sheikh El Toyor)

Family Bucerotidae

– Northern Ground Hornbill Bucorvus abyssinicus (Abu Duluk)

– African Grey Hornbill Lophoceros nasutus (Abu Mangur, Abu Tako)

– Red-billed Hornbill Tockus erythrorhynchus (Abu Mangur, Abu Tako)

Family Upupidae

– Eurasian Hoopoe Upupa epops (Hud hud)

Family Phoeniculidae

– Green Woodhoopoe Phoeniculus purpureus

– Black Scimitarbill Rhinopomastus aterrimus

Family Meropidae

– Red-throated Bee-eater Merops bulocki (El Warwar)

– White-throated Bee-eater Merops albicollis (El Warwar)

– Northern Carmine Bee-eater Merops nubicus (El Warwar)

– African Green Bee-eater Merops viridissimus (El Warwar)

– Blue-cheeked Bee-eater Merops persicus (El Warwar)

– Little Bee-eater Merops pusillus (El Warwar)

Family Coraciida

– Abyssinian Roller Coracias abyssinicus (El Tair El Khudari)

Family Alcedinidae

– African Pygmy Kingfisher Ispidina picta (A’geeb Kadab)

– Malachite Kingfisher Corythornis cristatus (A’geeb Kadab, Shineitir)

– Giant Kingfisher Megaceryle maxima (A’geeb Kadab)

– Pied Kingfisher Ceryle rudis (A’geeb Kadab)

– Grey-headed Kingfisher Halcyon leucocephala (A’geeb Kadab, Shineitir)

– Striped Kingfisher Halcyon chelicuti (A’geeb Kadab)

– Woodland Kingfishe Halcyon senegalensis (A’geeb Kadab, Shineitir)

Family Lybiidae

– Yellow-breasted Barbet Trachyphonus margaritatus (Abu Hatab, Berbeit)

– Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird Pogoniulus chrysoconus

– Vieillot’s Barbet Lybius vieilloti (Berbeit)

Family Indicatoridae

– Greater Honeyguide Indicator indicator (Kareima)

Family Picidae

– Nubian Woodpecker Campethera nubica (Abu Tag tag)

– Grey Woodpecker Dendropicos goertae (Abu Tag tag)

– Brown-backed Woodpecker Dendropicos obsoletus (Abu Tag tag)

– Lesser Kestrel Falco naumann

– Common Kestrel Falco tinnunculus

– Grey Kestrel Falco ardosiace

– Lanner Falcon Falco biarmicus (Abu El Kafat)

– Rose-ringed Parakeet Alexandrinus krameri (Shilleng, Babaga)

Passeriformes (Passerine families)

– White-crested Helmetshrike Prionops plumatus

– Western Black-headed Batis Batis erlangeri

– Northern Puffback Dryoscopus gambensis

– Black-headed Tchagra Tchagra senegalus

– Brubru Nilaus afer

– Black-headed Gonolek Laniarius erythrogaster

– Fork-tailed Drongo Dicrurus adsimilis (Mea’teb)

– African Paradise-Flycatcher Terpsiphone viridis

– Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio

– Woodchat Lanius senator

– Masked Shrike Lanius nubicus

– Pied Crow Corvus albus (Gurab)

– Dark-eyed Black Tit Melaniparus leucomelas

– Sennar Penduline Tit Anthoscopus punctifrons

– Northern Crombec Sylvietta brachyura

– Green-backed Eremomela Eremomela canescens

– Buff-bellied Warbler Phyllolais pulchella

– Grey-backed Camaroptera Camaroptera brevicaudata

– Red-pate Cisticola Cisticola ruficeps

– Red-faced Cisticola Cisticola erythrops

– Croaking Cisticola Cisticola natalensis

– Foxy Cisticola Cisticola troglodytes

– Tawny-flanked Prinia Prinia subflava

– Olivaceous Warbler

Hippolais pallida

– Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus

– Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica

– Ethiopian Swallow Hirundo aethiopica

– Sand Martin Riparia riparia

– Brown-throated Martin Riparia paludicola

– Common Bulbul Pycnonotus barbatus (Kadad El Dwak, Sukrug)

– Lesser Whitethroat Curruca curruca

– White-headed Babbler Turdoides leucocephala (El Gagag)

Yellow-billed Oxpecker Buphagus africanus (Tair El Gurad)

– Wattled Starling Creatophora cinerea

– Rüppell’s Starling Lamprotornis purpuroptera (El A’ak)

– Greater Blue-eared Starling Lamprotornis chalybaeus (El A’ak)

– African Thrush Turdus pelios

– Black Scrub-robin Cercotrichas podobe

– Pale Flycatcher Agricola pallidus

– Northern Black Flycatcher Melaenornis edolioides

– Snowy-crowned Robin-chat Cossypha niveicapilla

– Common Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus

– Common Stonechat Saxicola torquatus

– Northern Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe (El Gadieal)

– Isabelline Wheatear Oenanthe isabellina (El Gadieal)

– Black-eared Wheatear Oenanthe hispanica (El Gadieal)

– Beautiful Sunbird Cinnyris pulchellu (Massas El A’sal)

– Red-billed Quelea Quelea quelea (Gadum Ahmar)

– Northern Red Bishop Euplectes franciscanus (Tait El A’ish, Abu El GoKh)

– Fan-tailed Widowbird

Euplectes axillaris

– Lesser Masked Weaver Ploceus intermsdius (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Little Weaver Ploceus luteolus (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Northern mask weaver Ploceus taeniopterus (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Vitelline Masked Weaver Ploceus vitellinus (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Village Weaver Ploceus cucullatus (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Cinnamon Weaver Ploceus badius (Abu Dalo Dalo)

– Red-billed Firefinch Lagonosticta senegala (Tair El Ganna)

– Red-cheeked Cordon-bleu Uraeginthus bengalus (Tair El Ganna El Azrag)

– Crimson-rumped Waxbill Estrilda rhodopyga

– Black-rumped Waxbill Estrilda troglodytes

– Cut-throat Finch Amadina fasciata (Zabh El Rasul)

– African Silverbill Euodice cantans

– Pin-tailed Whydah Vidua macroura (Abu Mus)

– Sahel Paradise-whydah Vidua orientalis (Abu Mus)

– Village Indigobird Vidua chalybeata

– House Sparrow Passer domesticus (male known by the name ‘Wad Abrag while female known by ‘Ashusha’)

– Northern Grey-headed Sparrow Passer griseus

– Sahel Bush Pertoina Gymnoris dentata

– Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava (Um Geradoon)

– White Wagtail Motacilla alba (Um Geradoon)

– White-rumped Seedeater Crithagra leucopygia

– Yellow-fronted Canary Crithagra mozambic

Herpetofauna (Reptiles and amphibians)

The herpetofauna of Dinder National Park appears to be diverse and rich, yet poorly studied. Further research is essential to provide more details about the reptiles and amphibians that inhabit this diverse ecosystem. The list of species included in the text is based on the authors direct observations during the dry season and a small recent collection in the Sudan Natural History Museum. A total of 21 reptiles and 6 amphibians were recorded from the park.

The only species that experienced a decrease in numbers is the Nile Crocodile, which was eradicated from the park through organized government efforts. However, it has reappeared in the park and a few individuals were recorded along the Dinder River. Some crocodiles were released into the park by the Wildlife Administration.

Reptiles

Order Squmata

- Suborder Sauria (Lizards)

Family Gekkonidae (Geckos)

– East African House Gecko Hemidactylus angulatus (Dab)

– Sudani Dwarf Gecko Lygodactylus picturatus sudanensis

– Elegant Gecko Stenodactylus sthenodactylus (Dab)

Family Agamidae

– Doria’s Agama Agama doriae (Abu Fanela)

Family Varanidae

– Nile Monitor Varanus niloticus (Waral)

Family Scincidae

– Sundevall’s Writing Skink Mochlus sundevalli (Malja)

– Ocellated Skink Chalcides ocellatus (Malja)

– Rainbow Skink Trachylepis margaritifer (Sihliya)

– Five-lined Skink Trachylepis quinquetaeniata (Sihliya)

– Wingat’s Skink Trachylepis wingatii (Sihliya)

- Suborder Serpentes (Snakes)

Family Boidae

– Central African Rock Python Python sebae (Asala)

Family Colubridae

– Striped House Snake Boaedon lineatus

– Yellow-flanked Snake Crotaphopltis degeni

– Olive Sand Snake Psammophis mossambicus (Burul)

– Speckled Sand Snake Psammophis punctulatus (Abu Sa’aifa)

Family Elapidae

– Brown Forest Cobra Naja subfulva (Abu Darag)

Family Atractaspididae

– Sudan Burrowing Asp Atractaspis phillipsi (Abu Lakkaz, Abu A’shara Dagig, Abu Dafan El Aswad)

Family Viperidae

– Puff Adder Bitis arietans (Nawama)

Order Crocodylia (Crocodiles)

Family Crocodylidae

– Nile Crocodile Crocodylus niloticus (Timsah)

Order Testudines (Turtles and Tortoises)

Family Trionychidae

– Nile Soft-shelled Turtle Trionyx triunguis (El Terssa)

Family Pelomedusidae

– Adanson’s Mud Turtle Pelusios adansoni (Abu Rigiaba)

Order Anura (Frogs and Toads)

Family Bufonidae

– African Common Toad Sclerophrys regularis

Family Ranidae

– Natal Puddle Frog Phrynobatrachus natalensis

– Golden-backed Frog Amnirana gaiamensis

– Anchieta’s Rocket Frog Ptychadena anchietae

– Mascarene Rocket Frog Ptychadena mascareniensis

– Sudan Ridged Frog Ptychadena schillukorum

Fish Diversity

The rivers and mayas within Dinder National Park supports a diverse aquatic ecosystem with various fish species, predominantly representative of Nile River species. From the 168 species found in the Nile, it is estimated that over 40 species inhabit the park rivers and mayas. In the past, these water bodies served as undisturbed habitats for fishes, free from fishing activities. However, in recent years, the park’s administration has initiated commercial fishing in certain Mayas to increase park income. The potential impact of this activity on fish populations and diversity within the park remains unclear.

Partial List of Fish Species Confirmed from Dinder National Park

– Nile Bichir Polypterus bichir (Dabib El

Hut, Emsir)

– African Bonytongue Heterotis niloticus (Noak)

– Elephant Snout Mormyrus kannume (Khashm Ei Banat)

– Tiger-fish Hydrocynus brevis (Kass)

–Tiger-fishHydrocynus vittatus (Kass)

– Tiger-fish Hydrocynus forskahlii (Kass)

– True Big-scale Tetra Brycinus macrolepidotus (Kawwara Safsaf)

– Nurse Tetra Brycinus nurse (Kawwara himila)

– Characin Alestes dentex (Kawwara Baladi)

– Ray-finned Fish Distichodus brevipinnis (Khraish)

– Nile Distichodus Distichodus niloticus (Khraish)

– Moon Fish Citharinus citharus (Betkoya)

– Moon Fish Citharinus latus (Betkoya)

– Nile Carp Labeo niloticus (Dabs Kabir)

– African Carp Labeo coubie (Kadan)

– Assuan Labeo Labeo horie (Dabs Kabir)

– Bayad Bagrus bajad (Bayad)

– Bubu Auchenoglanis occidentalis (Humar El Hut)

– Golden Nile Catfish Chrysichthys auratus (Abu Riala)

– Werner’s Catfish Clarotes laticeps (Abu shanab)

– Silver Catfish Schilbe intermedius (Shilbaya)

– Egyptian Butter Catfish Schilbe uranoscopus (Shilbaya, Um Katif)

– North African Catfish Clarias gariepinus (Garmut)

– Mudfish Clarias anguillaris (Garmut)

– Engelsen’s Catfish Clarias engelseni (Garmut)

– African catfish Heterobranchus bidorsalis (Surta)

– Electric Catfish Malapterurus electricus (Barada)

– Wahrindi Synodontis schall (Gargur)

– Upsidedown Catfish Synodontis batensoda (Galabaya)

– Moustache Catfish Synodontis membranaceus (Galabaya)

– Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Bulti)

– Mango Tilapia Sarotherodon galilaeus

Arthropods Diversity

The arthropods of Dinder National Park are rich and diverse but poorly studied. Most studies focus on medically important species, mainly sandflies, and some economically significant ones, with few concentrating on specific groups like Odonata and ants. A study by Eisawi et al. recorded 165 species of ants from the park. The arthropods of Dinder represent Afrotropical species, including notable ones such as honeybees (Apis mellifera) collected by honey hunters, fungus-growing termites (Macrotermes sp.) characterized by their huge mounds, millipedes, centipedes, mantises, etc.

The arachnids of Dinder National Park are little known, with the potential for discovering new species. Many specimens of undescribed species of scorpions belonging to the genus Hottentota were collected from the park. Other arachnid species include Zeria funksoni, Pardosa oncka, Wadicosa fidelis, Pseudicius spiniger, Afrofilistata, Ocyale pilosa, Pardosa injucunda, and Plexippus paykulli. Our data on Dinder National Park’s arthropods are primarily based on dry-season collections during fieldwork in 2021 and 2022. One of the author’s main interests was Odonata, and 22 species were recorded from the park during the dry season, with three of them documented for the first time in Sudan. It is anticipated that arthropod diversity will be even richer and more diverse during the wet season.

List of Odonata recorded during the dry season in 2021 & 2023 from Dinder NP

Family Lestidae

– Pallid Spreadwing Lestes pallidus

Family Platycnemididae

– Northern Riverjack Mesocnemis robusta

– Little Featherleg Copera sikassoensis

Family Coenagrionidae

– Sailing Bluet Azuragrion nigridorsum

– Common Citril Ceriagrion glabrum

– Tropical Bluetail Ischnura senegalensis

– Swarthy Sprite Pseudagrion hamoni

– Nile Sprite Pseudagrion niloticum

– Bluetail Sprite Pseudagrion nubicum

– Wing-tailed Sprite Pseudagrion torridum

Family Aeshnidae

– Orange Emperor Anax speratus

Family Libellulidae

– Stout Pintail Acisoma inflatum

– Northern Banded Groundling Brachythemis impartita

– Broad Scarlet Crocothemis erythraea

– Black Percher Diplacodes lefebvrii

– Long Skimmer Orthetrum trinacria

– Phantom Flutter Rhyothemis semihyalina

– Ferruginous Glider Tramea limbata

– Violet Dropwing Trithemis annulata

– Silhouette Dropwing Trithemis hecate

– Red Basker Urothemis assignata

–Blue Basker Urothemis edwardsi

Threats to the Dinder National Park

There are many problems and threats to the ecosystems and biodiversity of Dinder National Park. The majority of these problems and threats are related to human activities within and outside park boundaries.

Hunting

Excessive hunting for large antelopes,birds and carnivore, driven by both food and as sports, as well as cultural practices such as the demand for leopard, serval, and python skins associated with societal status, has led to the decline and extinction of many species.

Mechanized Rain-fed Agriculture

Habitat loss resulting from the expansion of mechanized rain-fed agriculture since the 1960s within the park’s boundaries has cleared Acacia seyal cover from the park’s adjunct, disrupting migration routes and destroying critical wet-season habitats for many animal species. Mechanized rain-fed farms not only destroy wildlife habitats but are also associated with a decline in wild animals’ numbers due to hunting by individuals working in these farms, especially during the wet season when there are fewer rangers on duty and some animals migrate out of the protected area.

Livestock Trespassing

Illegal entry of livestock herds into the park poses a significant threat to wildlife. Traditionally, nomadic herds of sheep and camels move to the Butana plains during the wet season north of the park, returning to the Blue Nile, Rahad, and Dinder rivers for grazing during the dry season. However, the encroachment of mechanized rain-fed farms in these areas has forced nomads to enter the park. In recent years, large cattle herds belonging to the Ombraro tribe have been recorded grazing inside the park.

Nomads often usually kills large carnivores like lions and hyenas to protect their animals. Livestock entry into the park leads to competition for essential resources such as water and food with wild animals. Additionally, it can transmit diseases to wildlife, and vice versa, including anthrax and rinderpest. Diseases carried by livestock can have devastating effects on wildlife populations lacking immunity, evident in the rapid decline of reedbuck populations in the early 2000s. Furthermore, overgrazing by livestock contributes to habitat degradation, exacerbating the challenges faced by the park’s ecosystems.

A study carried out in 2021 confirmed the presence of large cattle herds inside core area of the park (10.7 individuals/km2) which represent the well protected area and about 30% present of park total size.

Climate Change

Climate change, compounded by severe droughts, has significantly stressed the park’s ecosystems. The severe droughts also increase displacement from western Sudan and West African countries to the park boundaries, intensifying pressure on wildlife from displaced populations. Until the 1970s, the area surrounding Dinder National Park was uninhabited by humans. However, by 1983, there were 20 villages surrounding Dinder National Park. In a 1993 population survey, 55,000 people were recorded living in 36 villages outside the park.

Charcoal Production and Trees Cutting

Dinder National Park stands as one of the last places in Sudan demonstrating a poor-savanna habitat, with most surrounding areas cleared of plant cover, evident from satellite maps. The clearing of tree cover increases pressure on the park for wood and charcoal production. Many charcoal producers have been arrested inside the park in recent years. The demand for energy by northern cities often drives charcoal making, leading to extensive deforestation of Acacia seyal and Combretum sp..

Furthermore, numerous trees inside the park are illegally cut for use in building and furniture making. Tree cutting and charcoal production can have detrimental effects on wildlife. Deforestation for these purposes results in habitat loss, disrupting ecosystems and reducing the availability of food and shelter for various species.

Fire

Fires usually occur for natural reasons during the drying season, but they also occur inside the park due to poachers and trespassing nomadic herdsmen. Honey collectors also use fire to gather honey from wild bees within the park. Fires exert diverse ecological impacts on Dinder National Park, depending on factors such as their frequency, intensity, and seasonality. The destruction of vegetation by fires disrupts habitats, altering plant and animal communities. It typically changes the tree community to species that resist it, such as Acacia seyal. A study in 1982 shows that in burnt areas, almost 90% of the regenerating trees are Acacia seyal.

Fishing

During the dry season, a few individuals from surrounding villages enter the park illegally to fish in the Mayas. They typically dry the fish and sell them as dried fish at local market centers. These dried fish are often buys by owners of mechanized rain-fed farms to feed laborers during the rainy season.

Moreover, in recent years, the park’s administration has introduced commercial fishing in specific Mayas as a strategy to increase park income.

Honey collection

The traditional collection of honey usually involves the use of fire, leading to uncontrolled wildfires that degrade the environment and result in a shift in tree cover towards fire-resistant species such as Acacia seyal.

Fruits and Wild Plants Collection

As the habitat in Dinder National Park remains healthy with a higher density of plant cover compared to the surrounding areas, local people from nearby villages often enter the park to collect wild fruits, plants, and herbs for food and traditional medicine. These items are also gathered in large quantities for sale in local markets. Commonly collected wild fruits from the park include Dom (Hyphaena thebaica), Nabag (Ziziphus sp.), Lalob (Balanites aegyptiaca), Tabaldi (Adansonia digitata), and Aradeib (Tamarindus indica).